The special story about a trophy watch; a Navitimer from Congo.

From Brussels to Congo; the expedition of 7 men in perspective.

By AWCo on 15 October 2019

There are times in life when you come across something extraordinary. Something with a story, a piece of history… An item whose value is defined by the imagination of the individual. Today, let us tell you about a trophy watch from a Belgian Lieutenant who performed something many of us can only dream of.

"It was 1949 when Belgium presented its plans to open a military base in Congo accessible by boat and air."

After World War II the United Nations was found. In the years after the war, many countries invested in military development in order to ensure world peace in the long run. It was 1949 when Belgium presented its plans to open a military base in Congo accessible by boat and air. In December 1949 the first landing strip was established already and further expansion continued right away to make the military training base ready for use. During this further expansion, a Major with the name Cassart came to the conclusion that a ground connection is essential to any military base in case boat and air connections would become difficult. With this note, Major Cassart introduced the most challenging obstacle yet for the already immense project.

The stage of Tilff From left to right: Cassart, Laurent, Leyder, Deventer, Gailly, Holvoet, Nagelmackers.

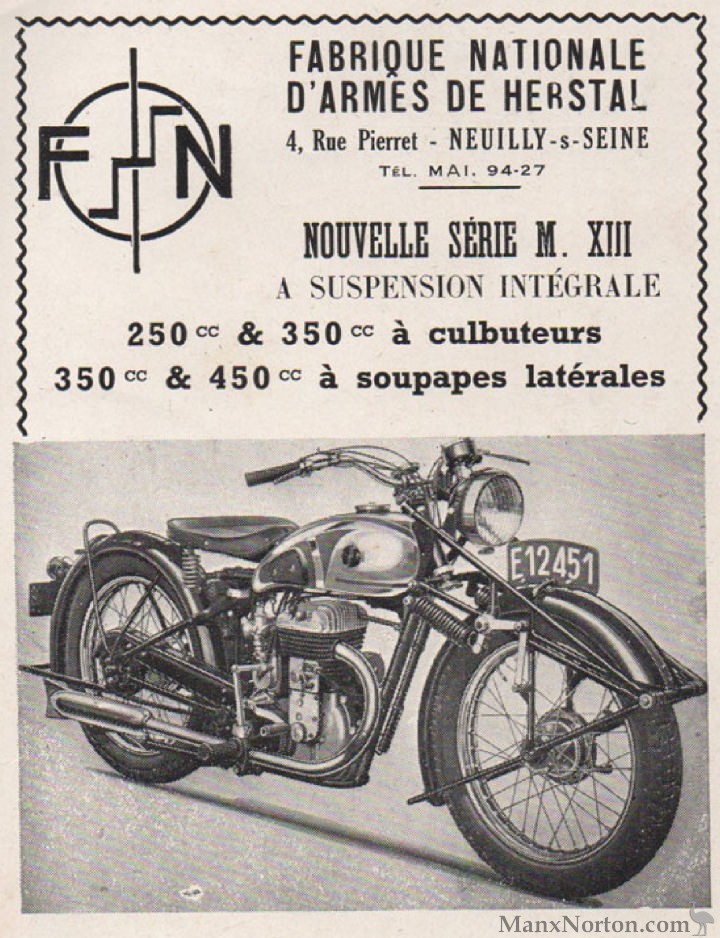

Cassart put himself in charge of a seven-man strong crew who would travel from Brussels to Congo by motorcycle to establish the ground connection to the military base. A 13.000 km long journey through the wind, fog, ice and desert on a clattering motorcycle. Comfort would play no part, neither would there be a trailing vehicle with supplies or spare parts. These men were on their own. To make sure the motorcycles would survive, two men got mechanical training ahead of the journey so they could fix the motorcycles in case they had a malfunction, and one of these two ‘mechanics’ was a Lieutenant named Jacques Holvoet who’d play a very important role during this expedition.

From left to the right: Leyder, Holvoet, Nagelmackers, Laurent, Cassart, Gailly

"...and this first part of the expedition already proved how challenging the circumstances would be."

The 9th of December 1950 was the day of departure; the seven men drove out of the Prince Albert base in Brussels and began their journey. The first destination was Marseille, and this first part of the expedition already proved how challenging the circumstances would be. Due to the icy roads, the first clutches were written off already at the French border. Nothing that couldn’t be fixed but so much for a good start… Before reaching Lyon Major Cassart had a collision resulting in a 50-meter road slide and burning wounds on his hands and more motorcycle difficulties would occur before reaching Marseille where they’d cross the Mediterranean Sea by ferry.

On December 13 the seven Belgians arrived in Algiers where they received a ceremonial welcome by a French military base. The French and Algerians were pretty skeptic about the motorcycle expedition since no man had ever crossed the desert on two wheels. Cassart’s reaction? ‘Even if we need to carry our bikes, we’ll succeed’. Luckily new spare parts for the bikes were sent to Algiers so they could continue their journey with slightly better odds.

"...just instinct for direction and drawn maps."

The desert might have been the most challenging terrain of them all. There was no existing trail or track, just instinct for direction and drawn maps. They had to drive on loose sand through the dust, almost suffocating both the carburetors and the drivers who could barely see. The soft wavy sand-scape is dangerous, come to a stop and you might never get your vehicle driving again. Therefore the bikes had to be driven at a speed of at least 60 km/h so they would ‘fly’ over the wavy loose sand. One time the squad even lost Cassart out of sight while driving through the desert and no one noticed until they arrived at the next meeting point. Cassart would arrive but alone and hours later. Luckily for him, his clutch didn’t give up on him with no one around.

January 11, 1951, the sand had disappeared and the landscape was filled with dense vegetation. They had overcome the desert. The new surroundings were an improvement compared to sand but still no hard roads or clear routes. After traveling through Nigeria and Cameroon, the Belgian adventurers reached the Congo border on January 17, which was a true milestone. The squad had ‘only’ 3000 km to go. When the 7 men arrived in Buta, the first big settlement in Congo, they were welcomed as ‘heroes’ by the locals who had heard about their journey.

At every following settlement, they arrived during the final phase of their journey they were welcomed and celebrated for their bravery and success until they reached the very south of Congo. The seven men finally reached Kamina, separately, but each man and motorcycle made it to the finish line and completed the 13.000 km long expedition, and so came an end to a crazy adventure. These men have earned their spot in history, respect.

The military base was destined to train commandos, pilots and parachutists. This brings us to Jacques Holvoet and his trophy watch. Lieutenant Holvoet was a military volunteer that fought in the War, worked his way up and later on joined the Special Air Service (SAS). During this military career, he was also trained as a parachutist and in 1952 he’d show that to the people in Congo. Together with Cassart and a few other members of the journey, Holvoet jumped out of a plane and performed the first parachute jump Congo had ever seen, leaving the local people flabbergasted, who’d never seen anything like that.

In the 1950s pilots and parachutists often wore a chronograph wristwatch so they could navigate with measured time and velocity if the traditional navigation equipment on the plain would fail. One of the most iconic watches used is the Breitling Navitimer without a doubt. In 1952 the Navitimer was born with three measuring scales in the rotating bezel purposefully built for pilots. Right away the logo of the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) appeared on the dial, which embodied the already obvious connection between Breitling and flying.

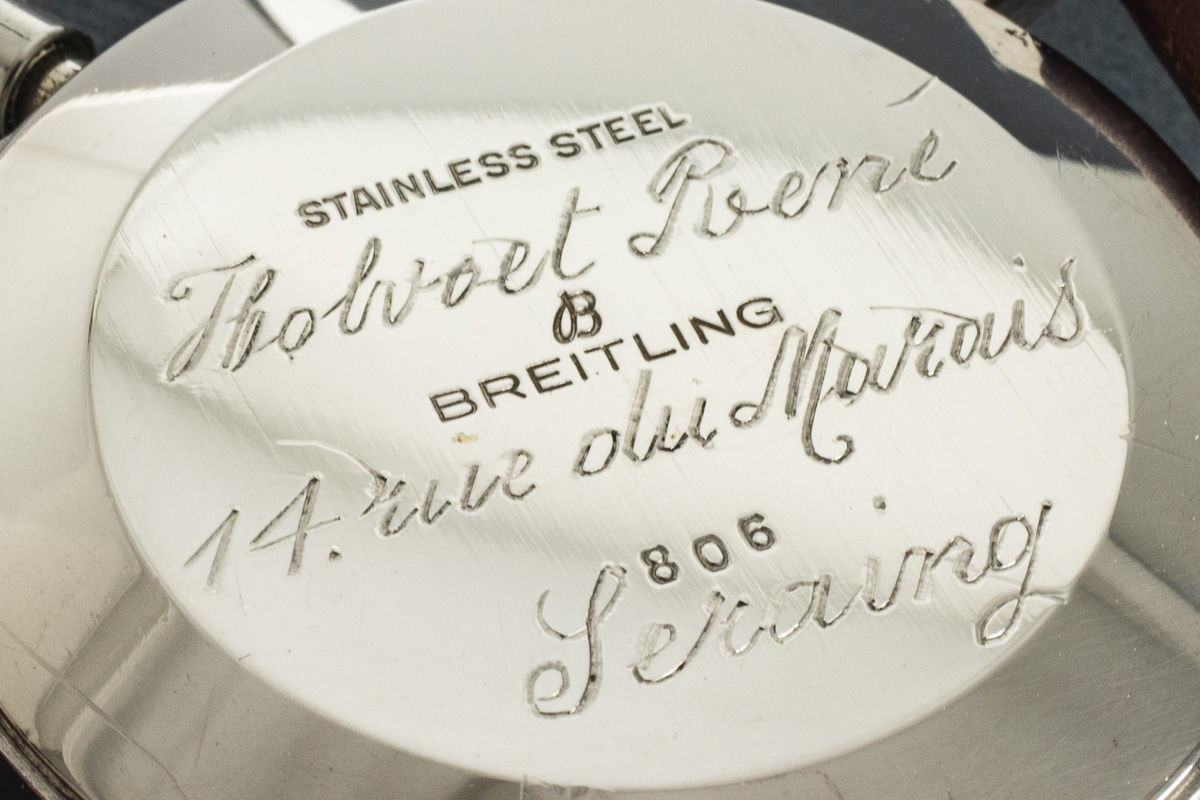

It was not uncommon that chronograph wristwatches were sold on military bases or were given away to important military staff, and that is how Lieutenant Holvoet acquired his timepiece. The Belgian hero was stationed in Congo for a few more years and that’s where he got his ‘trophy’ watch; the first Breilting Navitimer. Calling it a trophy watch may sound strange, however, today we can’t imagine parachutists receiving a Navitimer for delivered services, whereas it’s far more imaginable that Holvoet got his Breitling as a reward for his services. Whether he paid for it is something we’ll never know.

The Navitimer’s case-back is even engraved with his name and former address in case something happened to him, so the military could send it home…

Luckily that did not happen. After being passed on to the next generation, Lieutenant Holvoet’s watch was brought to the Amsterdam Watch Company by one of his descendants with the full story and some documentation. We felt that this Breitling deserved an article in tribute to Mr. Holvoet’s story ensuring its incredible heritage is preserved. The 806 Navitimer will soon be available to the public. Until then, stay tuned!